Your Dog Isn’t Sorry: The Science Behind The “Guilty Look”

It’s a scene familiar to countless pet owners. You walk through the door after a long day, only to be greeted by the remnants of a shredded shoe, an overturned trash can, or a suspicious puddle on the carpet. Your eyes scan the room and land on your canine companion, who is exhibiting what can only be described as the quintessential ‘guilty look.’ The head is hung low, the ears are pinned back, the tail is tucked, and the eyes avoid direct contact or gaze up with a look of profound sorrow. Our immediate human interpretation is clear: He knows he did something wrong. He feels bad about it.

This assumption, however, is a classic example of anthropomorphism—attributing human emotions and intentions to animals. While it’s a natural way for us to relate to our beloved pets, it may obscure what’s truly happening in our dogs’ minds. Is that look an admission of guilt, a canine apology? Or is it a far more primal, instinctual response that we are fundamentally misinterpreting? This article explores the fascinating science behind the ‘guilty look,’ debunking common myths and offering a deeper understanding of how our dogs communicate, how they perceive our reactions, and how we can use this knowledge to build a stronger, more effective relationship with them.

Deconstructing the ‘Guilty Look’: More Fear Than Remorse

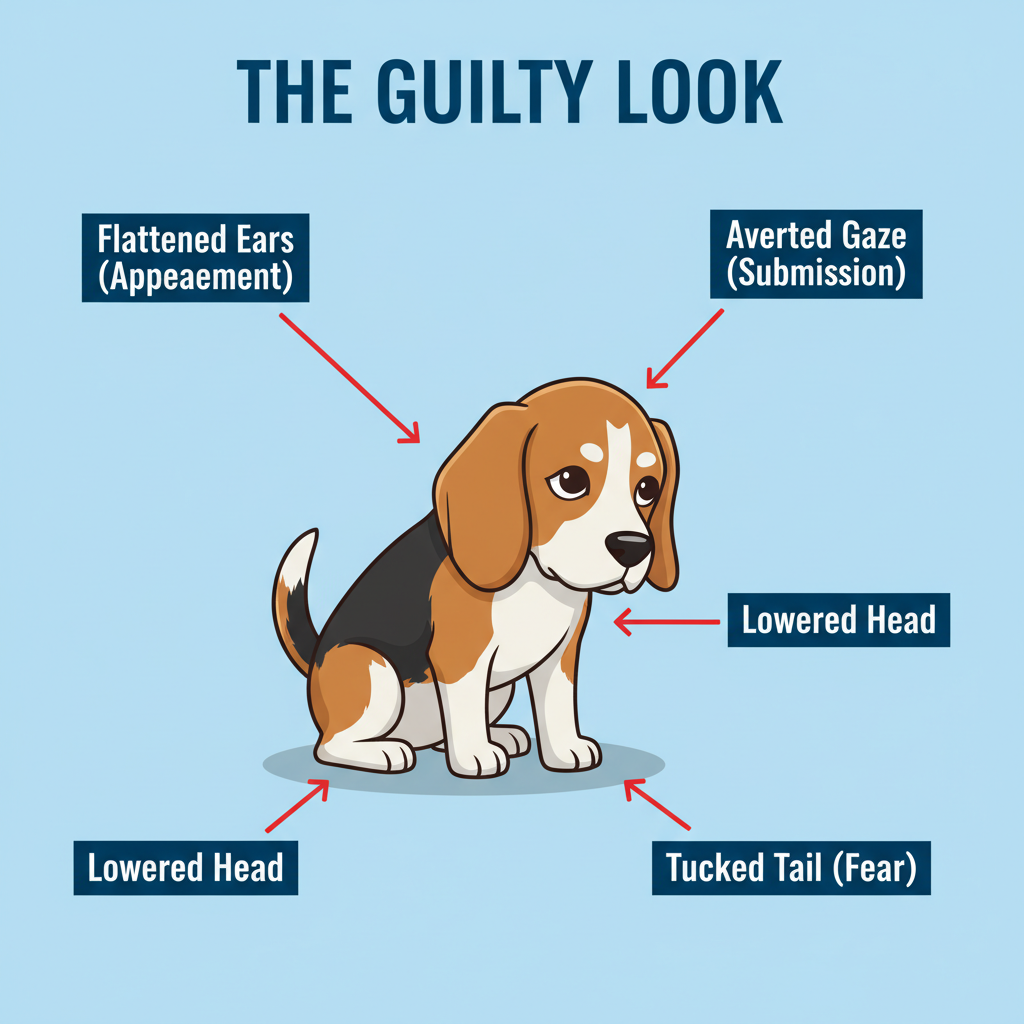

Before we can understand the motivation behind the behavior, we must first accurately identify what we are seeing. The ‘guilty look’ is not a single expression but a constellation of body language signals that are well-documented in canine ethology. Understanding these individual components is the first step in translating the dog’s true message.

Anatomy of Appeasement

When a dog displays the ‘guilty look,’ they are exhibiting a classic appeasement display. These are behaviors designed to de-escalate social tension and avoid conflict with a higher-ranking or perceived threatening individual. Key signals include:

- Averted Gaze: In the canine world, direct, sustained eye contact can be a challenge or a threat. A dog that avoids your gaze is signaling deference, not deceit.

- Lowered Head and Body: Making oneself smaller is a universal sign of submission. It communicates that the dog is not a threat.

- Tucked Tail: A low or tucked tail indicates fear, anxiety, or insecurity. It’s the opposite of the confident, high-held tail of a happy or assertive dog.

- Flattened Ears: Pinning the ears back against the head is another common signal of fear or submission.

- Lip Licking or Yawning: These are known as ‘calming signals,’ behaviors dogs use to pacify themselves and others in stressful situations.

When viewed through the lens of canine communication, this collection of signals doesn’t spell ‘guilt.’ Instead, it spells ‘anxiety’ and ‘fear.’ The dog is perceiving a threat—often, an upset owner—and is using its entire body to say, ‘Please don’t be angry with me. I am not a threat to you.’ This is a survival instinct, not a moral confession.

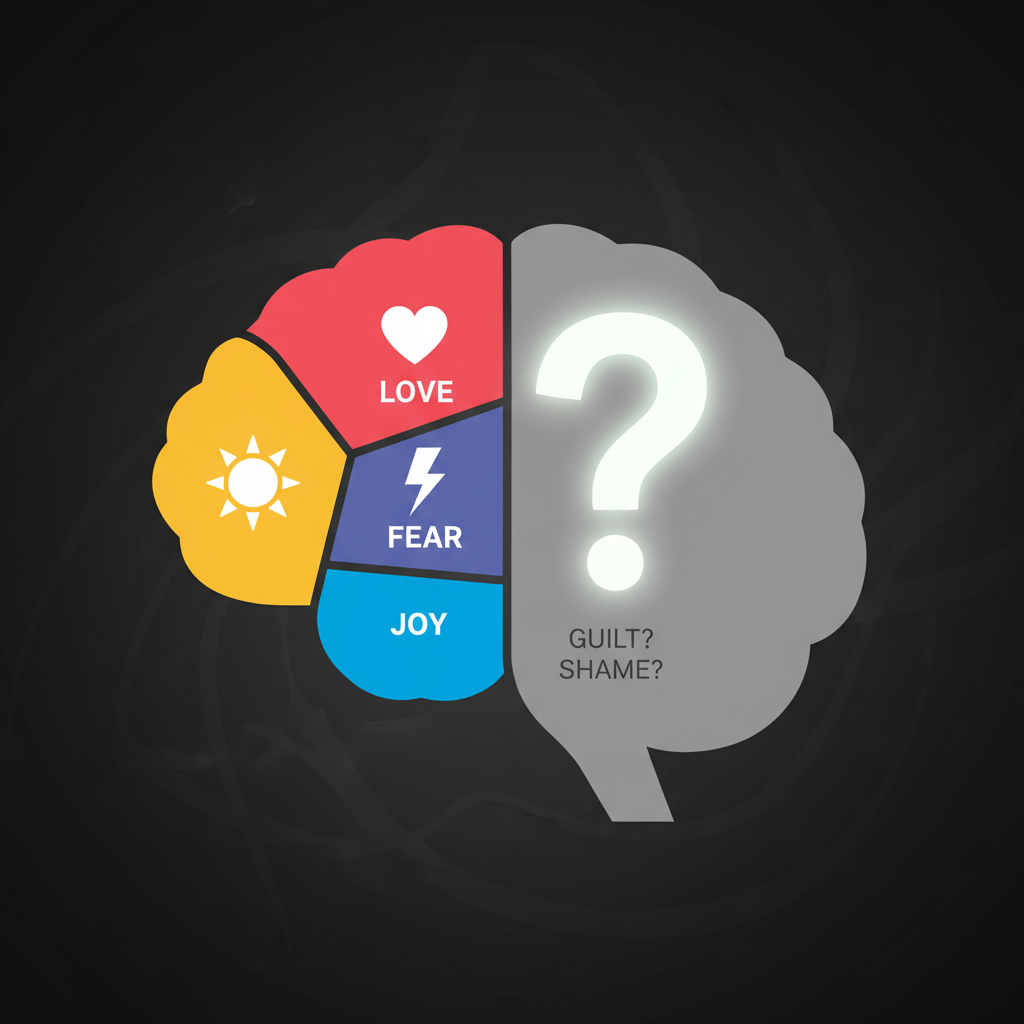

What Science Says: Primary vs. Secondary Emotions in Dogs

The scientific community largely agrees that dogs experience a rich emotional life. They feel joy, fear, anger, surprise, and love. These are known as primary emotions—the basic, instinctual feelings that are hardwired into the brains of many species, including humans. However, the concept of guilt is far more complex.

The Hurdle of Self-Consciousness

Guilt is a secondary, or self-conscious, emotion. Like shame, jealousy, and pride, guilt requires a sophisticated level of cognitive ability. To feel guilty, an individual must:

- Understand a set of rules established by someone else.

- Be aware that they have violated one of those rules.

- Be able to reflect on their past actions.

- Feel remorse for that specific violation.

Currently, there is no conclusive scientific evidence that dogs possess this level of self-awareness and moral reasoning. While their intelligence is not in doubt, their consciousness may not operate in a way that allows for such complex, self-reflective emotions. A landmark 2009 study by Dr. Alexandra Horowitz, a canine cognition expert at Barnard College, provided compelling evidence on this topic. In her experiment, owners left the room after telling their dogs not to eat a treat. In some trials the dogs ate the treat, and in others they did not. Regardless of whether the dog had actually eaten the treat, the researchers found that the dogs displayed more ‘guilty’ behaviors when their owners believed they had eaten it and scolded them.

The ‘guilty look’ was most strongly associated with the owner’s scolding tone and posture, not with whether the dog had actually committed the ‘crime.’ This suggests the look is a direct response to the owner’s cues in the present moment, not a reflection of a past misdeed.

Your Reaction Matters: How We Train the ‘Guilty Look’

If the ‘guilty look’ isn’t an admission of guilt, why is it so reliably performed when a dog has misbehaved? The answer lies in associative learning. Dogs are masters at reading our body language and tone of voice. They have learned to associate a specific context (e.g., shredded paper on the floor) with a specific reaction from their owner (e.g., anger, scolding, disappointment).

The sequence of events often unfolds like this:

- The dog, perhaps out of boredom or anxiety, shreds a pillow.

- The owner arrives home hours later, sees the mess, and becomes upset.

- The owner’s posture stiffens, their voice becomes sharp, and they may point at the mess or the dog.

- The dog, sensing the owner’s anger, immediately offers the appeasement signals we interpret as guilt.

- The owner sees this ‘guilty look,’ believes the dog ‘knows’ it did wrong, and may ease up on the scolding.

Over time, the dog learns that when a certain mess is present and the owner arrives, displaying these submissive behaviors can help de-escalate a tense and frightening situation. They are not feeling guilty for shredding the pillow hours ago; they are feeling scared of the angry human standing in front of them right now. They are reacting to your current emotional state, not their past actions. In essence, without meaning to, we have trained our dogs to ‘look guilty’ as a defense mechanism.

Moving Beyond Punishment: Effective Responses to Unwanted Behavior

Understanding that the ‘guilty look’ is a sign of fear, not remorse, has profound implications for how we should handle unwanted behaviors. Scolding a dog for a mess you discover hours after the fact is not only ineffective but can also be detrimental to your relationship. The dog cannot connect your current anger with its past action. All it learns is that your presence can sometimes be unpredictable and frightening, which can lead to anxiety and further behavioral issues.

A Proactive and Positive Approach

Instead of relying on punishment, which is based on a misunderstanding of canine cognition, a more effective strategy involves management and training. Here’s what to do when you find a mess:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Manage Your Emotions | Take a deep breath and stay calm. Avoid yelling, scolding, or using an angry tone. | Your anger only frightens your dog and damages your bond. It does not teach them the correct behavior. |

| 2. Remove the Dog | Calmly lead your dog to their crate or another room while you clean up. | This prevents you from taking your frustration out on them and removes them from the ‘crime scene’ without fanfare. |

| 3. Clean Up Quietly | Use an enzymatic cleaner for any potty accidents to eliminate odors that might attract them to the same spot. | A thorough cleanup without emotional reaction is the most productive immediate step. |

| 4. Address the Root Cause | Ask yourself why the behavior happened. Was it boredom? Separation anxiety? Lack of exercise? Insufficient house-training? | Destructive behavior is a symptom of an unmet need. Identifying the need is the key to preventing recurrence. |

| 5. Implement a Management & Training Plan | If the issue is boredom, provide more puzzle toys and exercise. If it’s separation anxiety, consult a professional trainer. If it’s house-training, go back to basics with a consistent potty schedule. | Proactive management (e.g., crating when you’re away, keeping shoes out of reach) and positive reinforcement for desired behaviors are the only long-term solutions. |

By shifting your perspective from punishing a ‘guilty’ dog to helping an anxious or bored dog, you transform the dynamic from one of conflict to one of compassionate guidance. This approach not only solves the behavioral problem more effectively but also strengthens the trust and security your dog feels with you.

Conclusion

The ‘guilty look’ is one of the most misunderstood behaviors in the canine world. It is a testament to our deep desire to connect with our dogs on a human level. Yet, true connection comes not from projecting our own emotional framework onto them, but from learning to speak their language. The science is clear: that sorrowful expression is not an apology, but a plea for peace. It is a reaction to our displeasure, a collection of appeasement signals designed to defuse a tense situation.

By letting go of the myth of the guilty dog, we can free ourselves from the ineffective cycle of delayed punishment and emotional reaction. Instead, we can embrace our role as proactive, compassionate leaders. When we see unwanted behavior not as a moral failing but as a cry for help—for more exercise, more mental stimulation, or more security—we can address the root cause of the issue. This shift in perspective is the key to a more harmonious home, a better-behaved companion, and a deeper, more authentic bond built on a foundation of mutual trust and understanding, not on misinterpreted guilt.