Reactivity vs. Aggression: Knowing the Difference Could Save Your Dog’s Life

The scene is a familiar one for many dog owners: a peaceful walk is suddenly shattered by an explosion of barking, lunging, and growling at the sight of another dog, a person, or even a passing car. In that chaotic moment, the word that often springs to mind is ‘aggressive.’ However, what you may be witnessing is not aggression, but reactivity. Confusing the two is a common and critical mistake—one that can lead to ineffective training, increased stress for both you and your dog, and in the most severe cases, tragic outcomes.

Understanding the fundamental difference between a dog that is reacting to a stimulus out of fear or frustration and a dog that is acting with true aggressive intent is the most important first step you can take toward resolving the behavior. It dictates your management strategy, your training approach, and your ability to keep your dog and your community safe. This comprehensive guide will dissect the nuances of canine reactivity and aggression, providing the clarity needed to interpret your dog’s behavior accurately and address the root cause with confidence and compassion. Getting this right isn’t just about better walks; it’s about protecting your dog’s future.

Defining Canine Reactivity: An Overreaction, Not an Attack

Defining Canine Reactivity: An Overreaction, Not an Attack

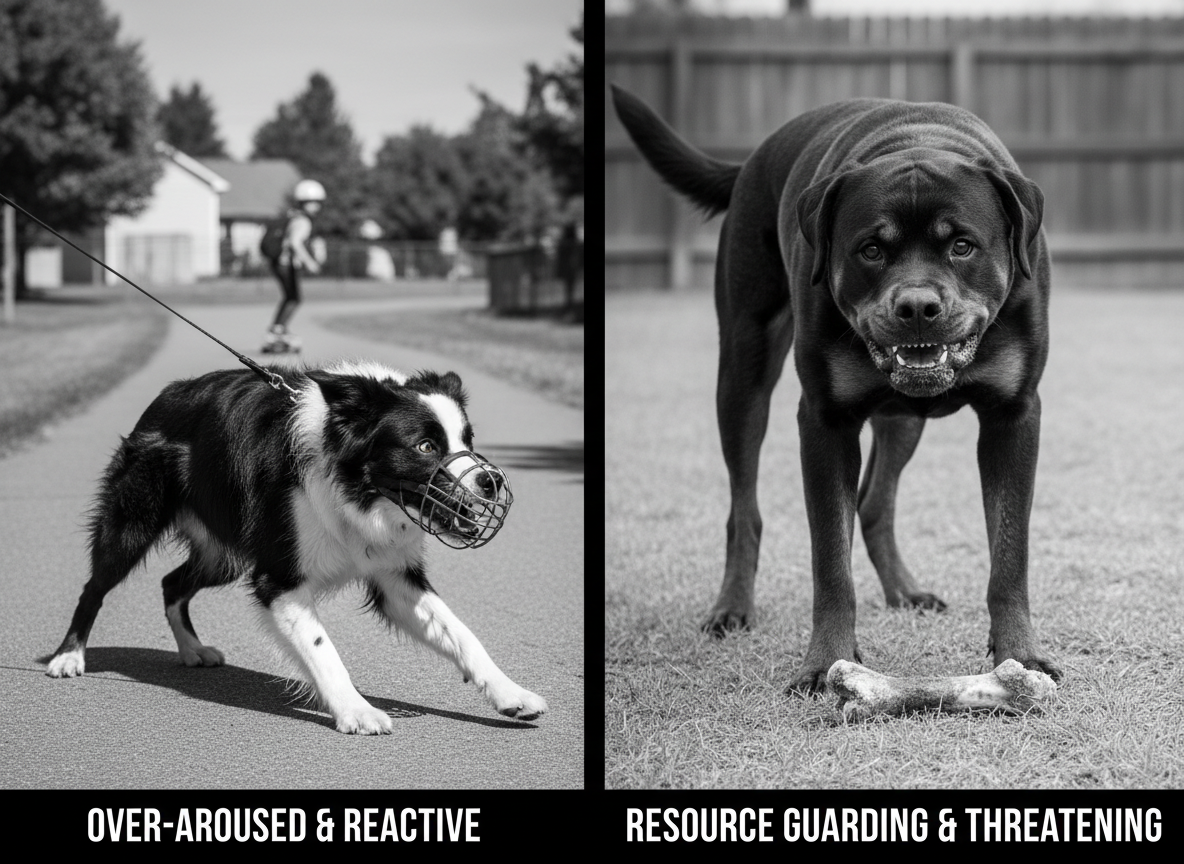

At its core, canine reactivity is an exaggerated or intense response to a particular stimulus, often referred to as a ‘trigger.’ It is not a character flaw or a sign of a ‘bad dog’; it is an outward manifestation of an internal emotional state, most commonly fear, anxiety, or frustration. Think of it as a dog having a ‘big emotional reaction’ that is disproportionate to the situation. A well-adjusted dog might see a skateboarder and ignore them; a reactive dog might see the same skateboarder and erupt into a frenzy of barking and lunging because the object is novel, fast-moving, and frightening.

Common Triggers for Reactivity

Triggers are highly specific to the individual dog, but some of the most common include:

- Other dogs (either all dogs, or specific sizes, breeds, or sexes)

- Strangers (either all people, or those with specific characteristics like wearing hats or carrying umbrellas)

- Moving objects like bicycles, skateboards, strollers, or cars

- Loud noises

- People or animals approaching the dog’s personal space, home, or vehicle

The Body Language of Reactivity

A reactive dog’s goal is typically to make the scary or frustrating thing go away. Their body language is designed to create distance. While it can look intimidating, it’s often a bluff. Key signals include:

- Lunging and Leaping: Often at the end of the leash, trying to move toward the trigger.

- Excessive Barking: High-pitched, frantic, or repetitive barking.

- Stiff, Tense Body: A rigid posture, often with weight shifted forward.

- Piloerection: Raised fur along the back and shoulders (raised hackles).

- Fixation: An intense, unwavering stare directed at the trigger.

Expert Tip: A key indicator of reactivity is that the behavior often diminishes or disappears entirely once the trigger is removed. The dog may be able to calm down relatively quickly after the other dog or person has passed.

Understanding Canine Aggression: The Intent to Harm

Understanding Canine Aggression: The Intent to Harm

Canine aggression, in contrast to reactivity, is defined by its intent. Aggressive behavior is any action intended to intimidate, threaten, or cause harm to another individual. While it can also be rooted in fear, it represents a dog that has crossed a threshold and is prepared to use physical force to resolve a conflict. Aggression is a form of communication, but it is the final, most serious warning before a physical altercation occurs, or it is the altercation itself.

Classifications of Aggression

Understanding the motivation behind aggression is key to managing it. Professionals classify aggression into several types:

- Fear-Based Aggression: The dog feels trapped and cornered and bites to defend itself. This is the most common type of aggression.

- Resource Guarding: Protecting valuable items like food, toys, bones, or even a specific person.

- Territorial Aggression: Defending their home, yard, or car from perceived intruders.

- Pain-Related Aggression: Lashing out due to an undiagnosed injury or chronic pain. A sudden onset of aggression always warrants a full veterinary workup.

- Protective Aggression: Protecting members of their social group (human or canine).

- Predatory Aggression: This is a distinct and dangerous form, characterized by silent stalking, chasing, and a powerful bite, often directed at smaller animals. It is instinctual, not emotional.

The Body Language of Aggression

The signals of an aggressive dog are often more direct and ominous than those of a reactive dog. The dog is not just trying to create distance; it is preparing for a confrontation. Look for:

- A Low, Rumbling Growl: This is a clear warning to back off.

- Snarling and Lip Curling: The deliberate display of teeth.

- A Hard, Direct Stare: Unblinking eye contact meant to intimidate.

- Stiff, Frozen Body: A chilling stillness often precedes an attack. The dog may lower its head and body.

- Snapping and Biting: An air snap is a final warning. A bite is the follow-through.

Unlike a reactive outburst that subsides when the trigger is gone, an aggressive dog may remain in a heightened state of arousal and may even pursue the target.

A Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions at a Glance

A Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions at a Glance

Discerning between these two complex behaviors can be challenging in a high-stress moment. The following table breaks down the primary differences across motivation, behavior, and intent to provide a clear, side-by-side comparison. Understanding these nuances is not an academic exercise; it directly informs how you should respond to and manage your dog’s behavior safely and effectively.

| Feature | Reactivity (The Overreaction) | Aggression (The Intent to Harm) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Motivation | Primarily driven by fear, anxiety, or frustration. The dog is overwhelmed and lacks the skills to cope. | Driven by a perceived need to control a situation, defend a resource, or cause harm. The dog is making a conscious decision to escalate. |

| Primary Goal | To create distance and make the scary or arousing stimulus go away. It is a defensive, distance-increasing behavior. | To dominate or eliminate a threat, protect a resource, or inflict injury. It is often an offensive, distance-decreasing behavior. |

| Typical Behaviors | Frantic barking, lunging on leash, whining, spinning, inability to disengage from the trigger. Often looks chaotic and uncontrolled. | Controlled, deliberate actions like stalking, freezing, growling, snarling, snapping, and biting. Often looks focused and purposeful. |

| Body Language Focus | Often a mix of offensive and defensive signals (e.g., tail high and wagging stiffly, but ears are back). Can appear conflicted. | Typically unambiguous offensive signals. A hard stare, stiff body, curled lip, and low growl are clear warnings of intent. |

| Recovery Time | The dog can often be calmed down and redirected once the trigger is removed from their sight or threshold. | The dog may remain in a heightened state of arousal long after the trigger is gone and may be more prone to redirecting on a nearby target. |

| Risk of a Bite | Lower, but not zero. A bite may happen if the dog feels cornered and its reactive display is ignored, but it’s not the primary goal. | Significantly higher. The behaviors are a direct prelude to a bite, which is the intended outcome if warnings are ignored. |

The Critical Overlap: When Reactivity Escalates to Aggression

The Critical Overlap: When Reactivity Escalates to Aggression

The line between reactivity and aggression is not always solid; it can be a porous boundary that some dogs cross. This escalation is one of the most compelling reasons to address reactivity seriously and proactively. A dog does not typically go from zero to biting overnight. The escalation often happens when a dog’s reactive signals are consistently ignored, punished, or misunderstood.

Imagine a dog that lunges and barks at other dogs out of fear. The owner, embarrassed, yanks the leash and yells. From the dog’s perspective, not only is there a scary dog present, but now its owner is also angry and adding pressure. The dog’s attempts to communicate its fear and desire for distance (‘Bark! Lunge! Get it away!’) have failed. Over time, the dog may learn that a simple lunge isn’t enough. It may conclude that a more intense display—a snarl, a snap, or even a bite—is the only way to make the threat retreat. This is a learned behavior known as ‘trigger stacking,’ where multiple stressors lower the dog’s threshold for a more severe reaction.

Important Takeaway: Punishing a reactive display (e.g., with a prong or shock collar) may suppress the outward behavior, but it does not change the underlying emotion. It can create a dog that no longer warns before it bites, making it significantly more dangerous.

An escalation from reactivity to aggression is a sign that the dog’s emotional distress has reached a critical level. It is a desperate attempt to control a situation in which it feels it has no other options. Recognizing this pathway is vital for intervening before the line is crossed permanently.

Management & Training Protocols: Your Action Plan

Management & Training Protocols: Your Action Plan

Addressing these behaviors requires a two-pronged approach: immediate management to ensure safety and prevent rehearsal of the unwanted behavior, followed by long-term training to change the underlying emotional response.

Step 1: Immediate Management

Management is not training; it’s about carefully controlling the environment to prevent your dog from being pushed over its threshold. You cannot train a dog that is already panicking.

- Increase Distance: Your dog’s leash is your best friend. See a trigger? Cross the street, turn around, or duck behind a parked car. Distance is the single most effective tool.

- Identify Thresholds: Learn at what distance your dog can see a trigger without reacting. This is their ‘sub-threshold’ distance, and it is where all training must begin.

- Avoid Trigger-Heavy Areas: For now, avoid the popular dog park or busy street fair. Opt for quiet sniff-walks in cemeteries, industrial parks on weekends, or quiet trails during off-peak hours.

- Use Appropriate Tools: A front-clip harness or a head halter can provide better physical control without causing pain, helping you manage lunging safely while you train.

Step 2: Long-Term Behavior Modification

Once management is in place, you can begin the slow and steady work of changing your dog’s mind about its triggers. The gold-standard methods are desensitization and counter-conditioning.

- Desensitization (DS): Gradually and carefully exposing your dog to a trigger at a low intensity (e.g., far away) where they do not react.

- Counter-Conditioning (CC): Changing your dog’s emotional response from negative to positive. This is done by pairing the sight of the trigger with something the dog loves, like high-value food (chicken, cheese, steak).

A simple DSCC exercise is the ‘Look at That’ (LAT) game. At a sub-threshold distance, the moment your dog looks at the trigger, mark the behavior with a ‘Yes!’ or a clicker, and immediately reward them with a super high-value treat. The dog learns: ‘Look at scary dog = get delicious steak from my human.’ Over many repetitions, the sight of the other dog begins to predict good things, changing the emotional response from fear to happy anticipation.

When to Seek Professional Help: Recognizing Your Limits

When to Seek Professional Help: Recognizing Your Limits

While many mild cases of reactivity can be managed by a dedicated owner, it is crucial to recognize when professional intervention is necessary. Attempting to handle serious behavior issues alone can be ineffective and dangerous.

Who to Call

The dog training industry is unregulated, so it’s vital to choose a qualified professional. Look for these credentials:

- Veterinary Behaviorist (DACVB): A veterinarian who has undergone extensive, multi-year training in animal behavior. They are the top experts and can diagnose medical contributions and prescribe medication if needed.

- Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist (CAAB): A professional with a Ph.D. or Master’s degree in animal behavior.

- Certified Dog Behavior Consultant (CDBC): A consultant certified by the IAABC with extensive experience in behavior modification.

- Certified Professional Dog Trainer (e.g., CPDT-KA, KPA-CTP): A trainer who has passed rigorous exams on humane, science-based training methods and has a proven track record with reactivity cases.

Avoid any trainer who recommends using pain, fear, or intimidation (e.g., shock collars, prong collars, ‘alpha rolls’). These methods are scientifically proven to increase anxiety and aggression.

Red Flags: Seek Help Immediately If…

- Your dog has bitten a person or another animal and broken skin.

- The behavior is escalating rapidly in frequency or intensity.

- The reactivity or aggression is unpredictable, with no clear trigger.

- Your dog redirects its frustration or fear onto you or other household members (e.g., biting your leg when it cannot get to another dog).

- You feel overwhelmed, frightened, or are no longer able to safely manage your dog.

Engaging a professional is not a sign of failure; it is a sign of responsible ownership. They can provide a proper diagnosis, create a safe and effective behavior modification plan, and give you the coaching and support needed to succeed.

Conclusion

Distinguishing between reactivity and aggression is the cornerstone of responsible dog ownership. Reactivity is a cry for help, an emotional outburst from a dog that feels overwhelmed. Aggression is a clear statement of intent, a final warning that a boundary is about to be crossed with force. While one can lead to the other, they are not the same, and they demand different levels of caution and intervention.

By learning to read your dog’s body language, manage their environment to ensure safety, and implement positive, science-based training protocols, you can do more than just control a behavior—you can heal the underlying emotion. For many dogs, this journey will require the guidance of a qualified professional. Seeking that help is a profound act of advocacy for your dog. Your dog’s life may very well depend on your ability to understand what they are trying to tell you and your courage to respond with empathy, patience, and the right expertise.