Nightmares or Seizures? Why Your Dog Growls in Their Sleep

The quiet of the night is broken by a low growl from your dog’s bed. You look over to see their legs kicking, their lips quivering. For any devoted pet owner, this sight triggers an immediate and pressing question: Is my dog having a harmless dream, or is this a medical emergency? The line between a vivid nightmare and a neurological seizure can appear blurry in a dimly lit room, causing significant anxiety. As a canine behaviorist and veterinary consultant, my goal is to dispel this uncertainty.

This guide will provide you with the definitive framework to differentiate between normal sleep vocalizations and the signs of a seizure. We will explore the science of canine sleep, detail the specific physical indicators of both events, and outline a clear action plan for what to do if you suspect a seizure. Understanding these differences is not just about easing your own fears; it is a critical component of responsible pet ownership that can ensure the health and safety of your canine companion.

Understanding the Canine Sleep Cycle

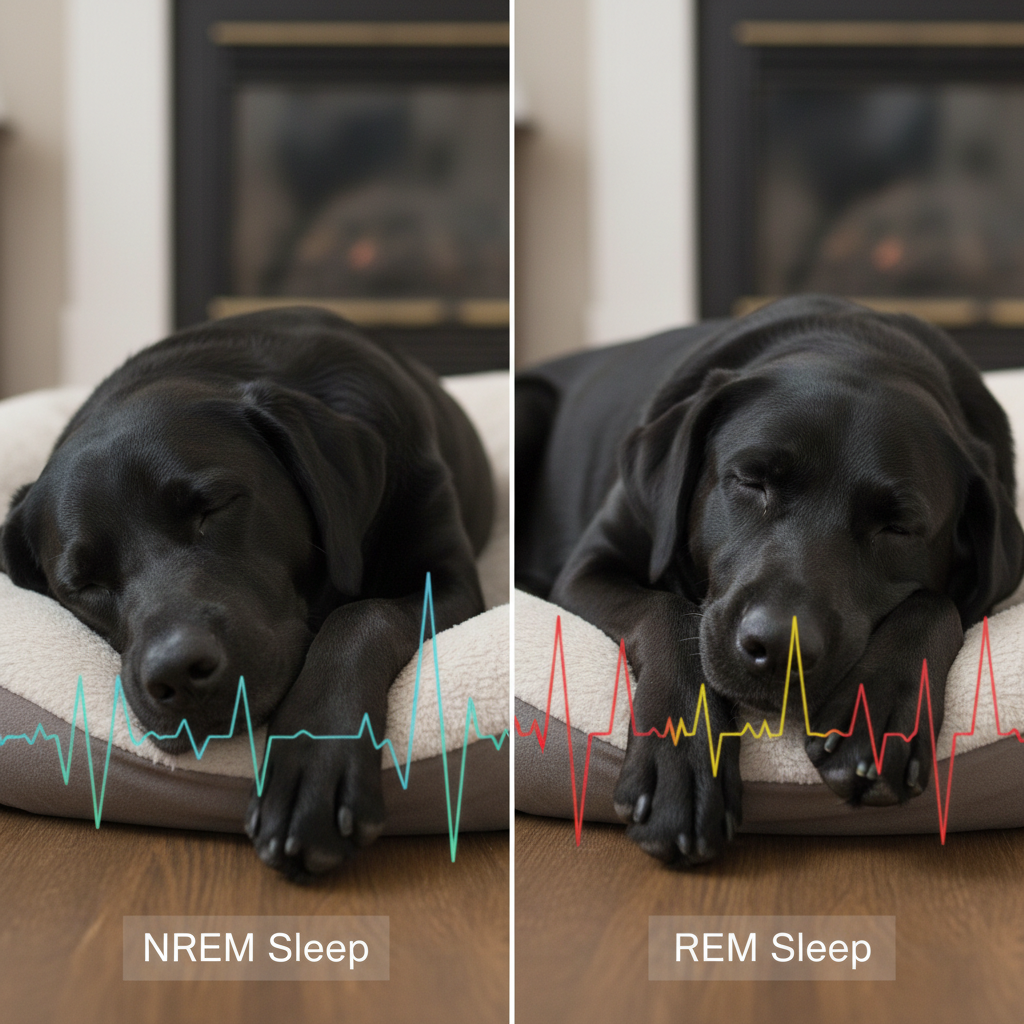

Before we can identify abnormal behavior, we must first establish a baseline for what is normal. A dog’s sleep is not a monolithic state of unconsciousness; it is a dynamic process with distinct phases, much like human sleep. The two primary stages are Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep.

During NREM sleep, which comprises about 75% of a dog’s sleep time, the brain’s activity slows down considerably. This is a period of deep, restful sleep where breathing is slow and regular, and the body is largely still. It is during this phase that the body focuses on physical restoration and repair.

The REM stage, however, is where the ‘action’ happens. This is the phase of active, dreaming sleep. Brainwave activity during REM sleep is remarkably similar to that of an awake, alert brain. It is during this period that you will observe the behaviors that often cause concern. The brain paralyzes the major muscles to prevent the dreamer from physically acting out their dreams, but this paralysis is not always complete. Small muscle twitches and involuntary movements can ‘leak’ through. This is why you may see your dog’s paws paddling, their face twitching, or hear them whimper, bark, or growl. These are all hallmarks of a healthy, normal REM sleep cycle and are simply outward expressions of their dream narrative.

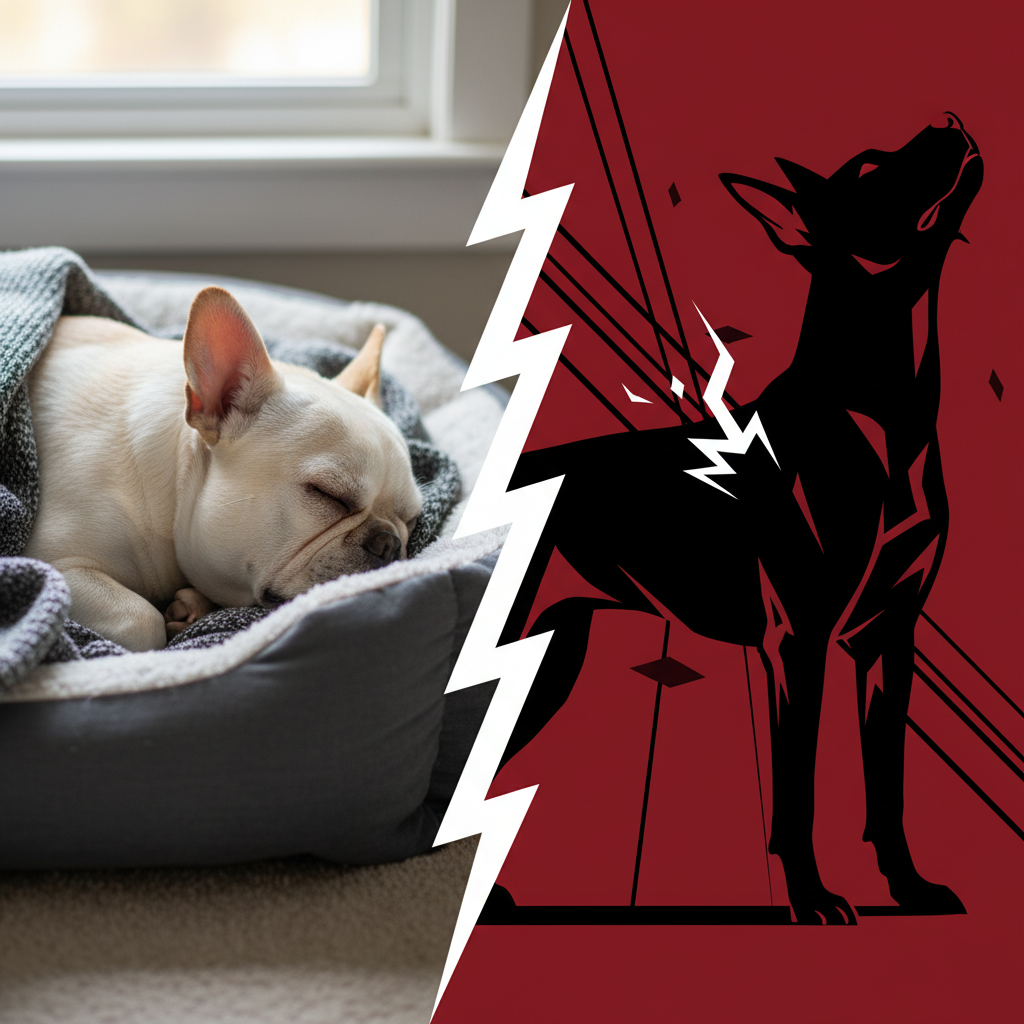

Signs of Dreaming: What Normal Sleep Behavior Looks Like

A dog deep in the throes of a dream can be quite the spectacle. These behaviors are involuntary and indicate a healthy, active mind processing the day’s events. It is crucial to recognize these signs as benign, preventing unnecessary panic or, equally important, disturbing your dog during a vital sleep phase.

Common Behaviors During Canine Dreams:

- Minor Muscle Twitching: You may notice subtle spasms or twitching in the paws, ears, whiskers, or lips. This is a classic sign of REM sleep.

- Gentle Limb Movement: The legs may paddle or kick gently, as if running through a field. The movement is typically soft and uncoordinated, not rigid or violent.

- Facial Expressions: A dog’s face is highly expressive, even in sleep. Look for quivering lips, a wrinkled brow, or the nose twitching as if sniffing something interesting.

- Vocalizations: Soft whimpers, muffled barks, quiet yips, and low growls are very common. These sounds are usually subdued, as if being made from a great distance.

- Rapid Eye Movement: Beneath the closed eyelids, you may see the dog’s eyeballs moving back and forth rapidly. This is the defining characteristic of the REM stage.

The most important distinguishing factor of a dream or nightmare is that the dog remains asleep but can be easily awakened. A gentle touch or a soft call of their name will typically rouse them. Upon waking, they may seem momentarily groggy or surprised, but they will quickly return to their normal, conscious state.

Recognizing a Seizure: Critical Warning Signs

In stark contrast to the gentle, disjointed movements of a dream, a seizure is a violent, systemic neurological event. It is the result of abnormal, excessive electrical activity in the brain. The physical manifestations are unmistakable once you know what to look for, and they are profoundly different from dream behaviors.

Hallmarks of a Grand Mal (Generalized) Seizure:

- Sudden Onset and Loss of Consciousness: The dog will collapse and be completely unresponsive. Calling their name or touching them will elicit no reaction. Their eyes may be open, but they are not ‘seeing’.

- Body Stiffness (Tonic Phase): The seizure often begins with the entire body becoming rigid and stiff. The head may be thrown back, and the legs extended rigidly. This phase typically lasts for 10-30 seconds.

- Violent, Rhythmic Convulsions (Clonic Phase): Following the stiffening, the dog’s limbs will begin to jerk or paddle violently and rhythmically. This movement is forceful and uncontrolled, not the gentle running motion of a dream.

- Jaw Chomping and Salivation: The dog may clamp its jaw, make chomping motions, and drool excessively or foam at the mouth. It is critical to keep your hands away from their mouth during this time.

- Loss of Bodily Functions: It is very common for dogs to involuntarily urinate or defecate during a seizure due to the complete loss of muscle control.

After the seizure ends, the dog enters a ‘post-ictal’ phase. This recovery period can last from minutes to hours. During this time, the dog may appear disoriented, confused, anxious, or even temporarily blind. They might pace aimlessly, bump into furniture, or not recognize you. This post-seizure confusion is a key indicator that a true neurological event has occurred.

Nightmare vs. Seizure: A Side-by-Side Comparison

To provide maximum clarity, a direct comparison of observable signs is essential. Use this table as a quick diagnostic reference, but remember that any concern warrants a professional veterinary opinion. The differences are often stark when observed carefully.

| Feature | Normal Dream / Nightmare | Neurological Seizure |

|---|---|---|

| Consciousness | Dog is asleep but can be awakened. | Dog is unconscious and completely unresponsive. |

| Body Movement | Gentle twitching, soft paddling, uncoordinated motions. | Begins with sudden stiffening, followed by violent, rhythmic, forceful convulsions. |

| Vocalization | Muffled, subdued whimpers, growls, or barks. | May be silent or involve loud, distressed vocalizations. Jaw chomping is common. |

| Eyes | Closed, with rapid, fluttering movement beneath the lids. | Often open with a fixed, vacant stare. Pupils may be dilated. |

| Bodily Functions | Full control is maintained. | Involuntary urination and/or defecation is common. |

| Aftermath | Wakes up normally, perhaps slightly groggy. | Followed by a period of profound disorientation, confusion, and potential temporary blindness (post-ictal phase). |

What Causes Seizures in Dogs?

A seizure is a symptom, not a disease itself. Identifying the underlying cause is the primary goal of the veterinary diagnostic process. The causes can range from genetic predispositions to acute medical emergencies.

Primary Causes of Canine Seizures:

- Idiopathic Epilepsy: This is the most common diagnosis, particularly in dogs between 6 months and 6 years of age. ‘Idiopathic’ means the cause is unknown, but it is widely believed to be an inherited genetic condition. Breeds like Beagles, German Shepherds, Labradors, and Golden Retrievers are more commonly affected.

- Toxin Ingestion: Many common household substances are potent neurotoxins for dogs. These include xylitol (an artificial sweetener), chocolate, caffeine, certain pesticides, and poisonous plants like sago palms.

- Metabolic and Electrolyte Imbalances: Diseases affecting other organs can trigger seizures. Kidney failure, liver disease, dangerously low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), or imbalances in blood calcium can all disrupt normal brain function.

- Brain Conditions: Structural problems within the brain can be a source. This includes brain tumors (more common in senior dogs), head trauma from an accident, or inflammatory brain diseases like encephalitis.

- Infectious Diseases: Certain viral or bacterial infections, such as canine distemper virus or rabies, can cause seizures, although these are less common in properly vaccinated dogs.

Your veterinarian will use a combination of your reported history, a neurological exam, and diagnostic tests like bloodwork to narrow down the potential causes and formulate a treatment plan.

What to Do If Your Dog Is Having a Seizure

Witnessing a seizure is frightening, but your calm and correct response can protect your dog from injury. Your primary role is to ensure their safety and observe key details for your veterinarian.

- Remain Calm and Do Not Panic. Your dog is not conscious and is not in pain during the seizure itself. Your anxiety will not help and may cause you to act rashly.

- Ensure a Safe Space. Do not attempt to restrain your dog. Instead, gently slide them away from stairs, sharp corners of furniture, or any other hazards. Place pillows or blankets around them if possible.

- Keep Your Hands Away from the Mouth. A seizing dog can bite down with incredible force involuntarily. They are not being aggressive, but it is a reflex. There is no risk of them ‘swallowing their tongue.’

- Time the Seizure. Use your phone’s stopwatch to time the event from the moment the convulsions begin until they stop. A seizure lasting more than five minutes is a life-threatening emergency (status epilepticus) requiring immediate veterinary intervention.

- Reduce Stimulation. Dim the lights, turn off the television or radio, and speak in a low, calm voice. This can help during the recovery phase.

- Cool Them Down. Seizures can cause a rapid increase in body temperature (hyperthermia). You can place a cool, damp cloth on their paws and belly after the convulsions have stopped.

- Contact Your Veterinarian Immediately. Once the seizure has ended, call your vet or the nearest emergency animal hospital. They need to know what happened, how long it lasted, and will advise you on the next steps.

Veterinary Diagnosis and Treatment Pathways

Following a seizure, a thorough veterinary workup is non-negotiable. The goal of the diagnostic process is to rule out underlying causes before arriving at a diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy. The veterinarian will start with a comprehensive physical and neurological examination, checking reflexes, gait, and cranial nerve responses.

The next step is typically a full blood panel, including a complete blood count (CBC) and a chemistry profile. This crucial test can identify metabolic problems, such as liver or kidney disease, hypoglycemia, or infections that could be triggering the seizures. If bloodwork is normal and the dog fits the profile for idiopathic epilepsy, your veterinarian may discuss starting treatment.

In some cases, particularly with older dogs or if seizures are difficult to control, advanced imaging may be recommended. An MRI or CT scan can visualize the brain’s structure and identify tumors, inflammation, or evidence of past trauma. Treatment for seizures is typically focused on management, not a cure. Anti-convulsant medications, such as phenobarbital, potassium bromide, or levetiracetam, are prescribed to reduce the frequency and severity of seizure activity. These medications require regular monitoring through blood tests to ensure therapeutic levels and check for potential side effects on organ function. The goal is to find the lowest effective dose to control the seizures while minimizing side effects, allowing the dog to live a happy, high-quality life.

Conclusion

The behaviors our dogs exhibit in their sleep offer a fascinating glimpse into their minds, but it is our responsibility as their guardians to interpret these signs correctly. While a growl or a running motion in sleep is almost always the harmless byproduct of a vivid dream, understanding the stark, violent signs of a seizure is a life-saving skill. The key differentiators are consciousness, body rigidity, and the confused, disoriented state that follows a true neurological event.

Never hesitate to act on your concern. If you are ever in doubt, attempt to safely record a video of the episode to show your veterinarian. This visual evidence is invaluable for an accurate diagnosis. By arming yourself with this knowledge, you move from a position of fear to one of empowerment, ready to provide the best possible care for your loyal companion, whether they are chasing squirrels in their dreams or facing a medical challenge that requires your steadfast support.